Every Perfectly Imperfect recommendation is a reflection of taste.

Everyone’s taste is different, but many of us formed ours the same way: by scouring the internet, researching, and cataloging everything that interests us. The phenomenon has existed since the early days of the internet, before everything became a product sold to us through algorithms and advertisements.

Our new column, Browser History, is about these formative early internet experiences — the memories of forums, message boards, chat rooms, and other bits of internet ephemera that shaped the taste of today.

We're very excited to kick this off with a piece from Brad Philips. He's one of my favorite writers, an early PI guest, a Pi.FYI user (@BRAD-PHILLIPS) and more recently - a friend.

Enjoy <3

In 1990 I was sixteen years old, and unhappy. I had a few friends at school, and a few in my neighbourhood, but I wasn’t exactly thriving socially.

I was a weird teenager, with atypical interests. Other boys my age liked hockey. I liked tennis, and inexplicably, cricket. Other kids my age were getting their driver’s licenses. I was agoraphobic, and scared to be in a car. All the Bretts and Todds and Matts in my school hated being assigned books for English Lit. I read voraciously, and was grateful for the escape I found in other people’s stories. During a week spent home, sick, I called the local consulates, requesting pamphlets about their countries. After long days spent feeling out of place at school, I loved coming home to overstuffed envelopes bearing my name, full of information about Egypt, Denmark or Sudan. Corresponding with consulates was one technique I devised to explore the world beyond the stultifying, uninspiring suburb I was growing up in.

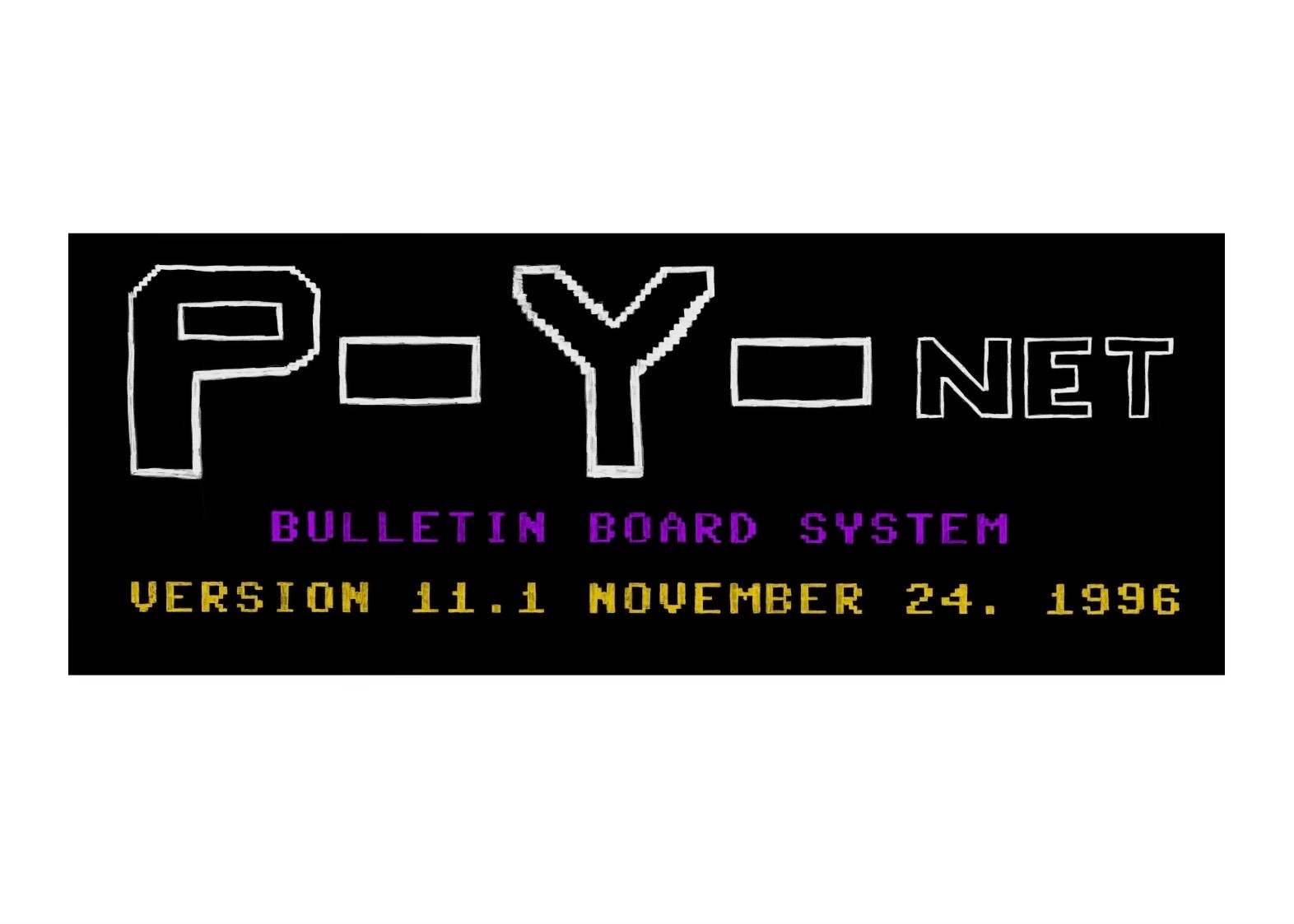

Christmas of that year my accessibility to the larger world exploded. My strange second cousin Roger—allegedly a nudist and swinger—gifted me a modem. Soon, a small squeaking box in my bedroom became every book, every consulate, every obscure sport in the world. After school I’d come home, eat dinner, then lock myself in my room. I was both student and professor in a classroom of my own design, free to educate myself as I saw fit, without concern for failing grades. Logging onto the internet, my modem sounded like a troop of chimpanzees cannibalizing each other. The internet of 1990 was crude, but at the time it seemed miraculously sophisticated. I found Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs) devoted to various subjects, subjects more obscure than I ever would’ve dreamed of. I can’t remember precisely, but they might’ve been:

LONG-HAUL TRUCKER LIFE

GOTHIC POETRY

KARATE IN BULGARIA

SHERLOCK HOLMES EROTICA

OFFICE FURNITURE RESALE

POLICE AND FIREFIGHTER ROMANCE

MACON GEORGIA MAYORAL RACE GOSSIP

CAKE DECORATION

You get the idea.

This column is about nostalgia for the early internet, for time spent online unguided by algorithms, and not bombarded by advertising. Today the internet shows me what I already like, or directs me to things that reinforce my views, tastes and opinions. As a result, my interaction with the internet of the present hasn’t facilitated much growth, or generated novel experiences. There’s a growing sense that capitalism’s impact on technology has engendered a troubling tribalism, a decrease in critical thinking, and a helpless submission to overwhelming sameness. Here are some things that happened to me twenty and thirty-plus years ago, when life online involved active exploration more than it did passive consumption.

In 1991 I joined — and I blush to admit it — a poetry bulletin board. There I met a guy named Ian, a graduate student at the University of Toronto, who wrote poetry only slightly less awful than mine. We met for coffee one day in the city, and the following year, Ian and his girlfriend Betsy drove me and my girlfriend Harmony to Lollapalooza 2 in Barrie, Ontario, where I saw Ministry, Body Count and The Jesus and Mary Chain. I knew I liked two of those bands, and by discovering I liked the third, my musical tastes broadened. I also got brutal heatstroke, and spent the last third of the day half-passed out under Ian’s Volvo, waiting for him to return so we could drive back to Toronto.

In 1993, by way of another bulletin board — this one devoted to trivia — I met a guy named Michael, who spent his nights breaking into restricted public areas and photographing them for his zine, which was the centre of a large, secret, international community of urban explorers. Every second Wednesday, Michael hosted a trivia night at a local pub called Thursdays. One Wednesday I decided to check it out, and met Michael’s bizarre crew of overeducated weirdos, each of whom were more deeply online than I was. Through some of these people, I met a girl who’d briefly be my wife. Through that wife I was exposed to art history, which was her major. While she was at school I devoured her textbooks, and received a fairly comprehensive vicarious education. She was insanely knowledgeable about art and ideas, and helped me to understand things that were far beyond the comprehension of my rather simple mind. We also went to Italy, a country I never would’ve visited, because she wanted to see some paintings that were important to her thesis. In Italy I visited the Scrovegni Chapel, which contains a fresco by Giotto from 1305. I had a religious experience in that building, my first and last. So it’s only because of Michael and his Wednesday trivia night at Thursdays that today I can say I believe in God.

Of course there’s more. I’ve always been inclined to distract myself with the internet, for better or worse. Before social media, I’d play Scrabble for hours at isc.ro, a website hosted in Romania and the virtual homebase for people addicted to—and professionally competing at— Hasbro’s family friendly word game. After hours of online Scrabble, I used to then sit on my porch, chain-smoking and reading books. Not today. Today I stay online, and instead of smoking cigarettes I suck nonstop on a pastel colored vape like an unsoothable infant. Instead of reading books I stay online, because I have no choice, because all of my business can be conducted on the Apple product in my hand. And because everyone else has this same Apple product, and is equally able to conduct their business while on the toilet—or while rocking their child to sleep, while driving on the highway, while at their mother’s funeral—we’re all both forever available and never quite present, answering emails, hearting texts like toddlers, infantilized by smartphones more technologically sophisticated than Apollo 11, which allegedly landed on the moon in 1969.

Today I need my phone and thus the internet to board a plane, to ride the subway, to do countless things I used to do without a phone, or the internet. I’m told this is good for me, that it’s more convenient, that my life is simpler now. I’m not convinced.

I quit smoking cigarettes in 2021 because they were incredibly, obviously bad for me, and switched to vaping. I thought this was wise; a healthier way to satisfy my nagging addiction to nicotine. I used to smoke a pack of cigarettes a day. Today I vape essentially without pause. Indoors and outdoors, in the subway and in bed, all day, everyday. This is great I tell myself, you’re taking care of your body, there’s no tar, no strychnine. I try to ignore that my heart is always racing in a way it wasn’t when I just smoked cigarettes, that these cheap plastic objects are made in unknown countries, most likely by children, and are absolutely unregulated. I make an absurd, almost suicidal leap of faith each time I suck on my Elfbar Miami Mint, and writing it down I can see that it’s insane. Cigarettes equal bad, vaping equals less bad; less bad equals good. That’s as sophisticated as my math gets on the subject. This neanderthal level equation seems to have been applied to the internet—internet good, more internet more good—and now we’re all wandering around with our heads down, bumping into each other on the street, raising children destined to be become adults with crippling attachment disorders, because each time they looked up at their parents for comfort or connection, their parents were staring at their phones, not at them.

Jack Bush was a Canadian artist who began his career as a commercial illustrator. Miserable at his job, he began seeing a psychiatrist, who recommended Bush devote one room in his house strictly to artistic experimentation. Bush took his shrink’s advice, and spent time in a locked room, pushing pigment around on paper and canvas, unconcerned with what it meant, or whether his client would be happy. As a result, he became an accomplished abstract painter and caught the attention of Clement Greenberg—the critic and preeminent champion of Abstract Expressionism—who would become something like Bush’s mentor. During studio visits, Bush would show Greenberg three, four paintings that he’d made which were stylistically similar. Greenberg would tell Bush that to be truly successful, he needed to make twenty, thirty versions of the painting, as more successful artists like Mark Rothko were doing. Bush refused on the grounds that, if he made more than necessary—more than three or four—it would begin to feel like production, like work, like the very thing he’d constructed this private room in his home to find freedom from. As a result, Bush is not the household name that Rothko is. Important to note is that Rothko died after eating a handful of barbiturates and opening an artery in his wrist like an envelope with a razor blade, whereas Bush died at sixty-seven of an old-fashioned heart attack.

This story encapsulates my feelings about the internet, today, as someone who’s experienced life both before and after the introduction of a world expanding technology. As a teenager, access to that early internet was exciting, promising; it allowed me to see beyond the stifling myopia of my suburban upbringing. But as is essentially always the case when capitalism enters the scene, what once seemed promising proved disappointing, and what once felt exciting has begun to feel routine, limiting, even oppressive. To be online in 2025 feels like being at work, and there’s often a felt obligation to produce, hustle, brand and rebrand. Of course, it’s true that people still discover new bands, new interests, new people and new experiences, but today that’s mostly despite the way the internet works, not because of it.

I don’t want to be a bummer. I’m not young, and I don’t know the experience of young people. Maybe they’ve grown up totally satisfied by the internet, and can attribute much of their development to helpful algorithms which steered pleasant information into the streams of their attention. I really don’t know. I do know that some young people I know own dumbphones because they resent the obligation to always be online. People my age need to be wary of engaging in ‘it was better back when’. Tony Soprano once said that ‘remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation, and I think that may be true. But sometimes it really was better way back when. In this column, I’ll interview people about their own early experiences with the internet. Maybe their perspectives will help me understand what’s valid, and what’s just the whiny nostalgia of a man my age. And in this column I’ll write about my own experiences with both the new and old internet. In the last three decades I’ve occasionally been very online. Some people know me as that guy, the internet guy. I’ve never felt like him, but maybe that’s who I am, or who I appear to be. Whatever this becomes, I hope it offers novelty, and never feels routine, predictable, or like that most terrible of things, work.

PERFECTLY IMPERFECT IS A CULT FAVORITE NEWSLETTER AND AN APP FOR YOUR RECOMMENDATIONS